Key Books That Address This Moment

audio Introduction

By David Bowles

@DavidOBowles

Serving as chair of the Young People’s Literature panel for the National Book Awards in 2025 meant reading deeply, with an eye not just toward excellence of craft, but toward resonance. The questions that we judges kept returning to were simple: What are young readers living through right now, and which books are brave enough to meet them there?

From hundreds of titles, a handful stood out not merely for quality, but for their ability to speak honestly to grief, precarity, injustice, heritage, and survival in ways that feel unmistakably of this moment. While we recognized finalists and a winner, I wanted to draw your attention to five other books, drawn from last year’s reading, that offer powerful answers.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Invisible Parade by Leigh Bardugo, illustrated by John Picacio. I literally wept when reading this one. Few recent books so gently and effectively address collective grief. Anchored in the image of a procession of ancestors—European, Indigenous, and Mestizo—The Invisible Parade offers Mexican American children a framework for resilience rooted in continuity rather than erasure. In a time when loss has become ambient background noise for many families, this book affirms that survival is not solitary. The language is spare, allowing the stunning and richly layered art to do the work of reminding all of us that we are accompanied, even when we feel most alone.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

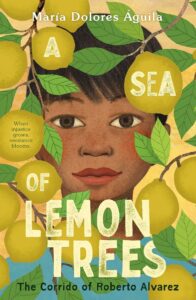

A Sea of Lemon Trees by María Dolores Águila. Every day, I’m reminded that history does indeed repeat itself: not metaphorically, but materially. This necessary novel-in-verse recounts the story of Roberto Álvarez and the fight for education equity in 1930s California, part of a national struggle that would last four decades (giving rise to a better system that is already being dismantled). By confronting a past moment of displacement and dispossession that echoes uncomfortably with our present, the author allows young people to recognize patterns of exclusion before they calcify into inevitability. The narrative’s greatest strength is refusing to let history feel sealed or distant. Instead, it insists on relevance, challenging readers to see the moral throughlines between then and now.

A Bird in the Air Means We Can Still Breathe by Mahogany L. Browne. As the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic is officially erased before our eyes, this book sings out reminders like a divine chorus, polyphonic and wise. Its use of Trinidadian Creole alongside standard English is intentional and structural, embodying the hybridity of identity and voice that an increasing number of young folks in the US inhabit daily. In a moment when masking and breath itself have become politicized (pandemic, protest, policing, and perpetual environmental collapse), Browne’s innovative and necessary text insists on collective endurance and the power of speaking in one’s own rhythms.

The Story of My Anger by Jasminne Méndez. In a cultural moment when young BIPOC students are routinely disciplined for expressing anger, this screenplay-inflected novel-in-verse feels both urgent and necessary. Centering Yuli’s Black Afrolatina identity, the book refuses the erasure that often accompanies Latinidad in children’s literature, insisting instead on the visibility of Blackness within it. Yuli’s anger is not abstract or generalized; it is forged in specific injustices, including her confrontation with a racist drama teacher who polices her voice and ambition, and her experience navigating book banning in a Texas school system determined to silence stories like her own. The narrative treats anger not as a behavioral problem but as a rational, clarifying response to systemic harm. What makes the book especially resonant is its insistence that naming injustice, whether in a classroom or a library, is itself an act of self-preservation. Méndez gives young readers language not only for how anger feels, but for why it exists, and what it can demand.

The Incredibly Human Henson Blayze by Derrick Barnes. Children’s literature is increasingly asked to choose between imagination and truth, but the latest by Derrick Barnes insists on both. Drawing on the elastic logic of tall tales and a strain of magical realism that feels deeply rooted in Black Southern storytelling traditions, the novel blurs the line between the impossible and the emotionally true. That playfulness, however, is anything but escapist. Instead, it’s used to underscore the heroism of its protagonist as he stands not against oversized legendary obstacles, but the intransigence of a community that wants him to be an athlete on display rather than a champion of justice. Threaded through Henson’s outsized adventures is a determined effort to surface histories that right-wing leaders are actively working to excise from school curricula—stories of community resilience, racial injustice, and local memory that refuse to be flattened or forgotten. What makes the book so timely is its refusal to abstract childhood: this is a story rooted in neighborhood dynamics, peer accountability, and the messy ethics of belonging. It trusts young readers to recognize themselves not as symbols, but as participants in community, capable of growth, missteps, and moral imagination.

Now, it will come as little surprise to anyone who knows me that I think of these five novels as frankly outliers amid the thousands of books published for kids each year. As the current reactionary political movement has tightened its grip on freedom of expression, many publishers and other gatekeepers have preemptively bent the knee, demonstrating the shallowness of their commitment to authentically and responsibly reflecting demographic realities in the books they promote. The young people in these five novels evince more courage than most adults in publishing and education.

However, another thing the books share is a refusal to flatten experience. And that, setting aside anticipatory obedience to authoritarianism, is where publishing still struggles. Too often, “representation” is treated as singular and monolithic: one migration story, one grief narrative, one queer coming-out, one disabled perspective standing in for an entire constellation of lived realities. But underrepresented communities do not have a single story, nor even a dominant one.

What’s missing is sustained investment in intragroup diversity: books that acknowledge difference, contradiction, class variance, regional specificity, and disagreement within communities. We need more stories that resist symbolic overwork (in which a single character is asked to represent an entire people) and more that allow young readers to encounter themselves as complex, plural, and sometimes unfinished.

For the most vital books of this moment don’t restrict themselves to declaring, “This is what it means to be X.” Instead, they affirm, “This is one truth, lived fully, and there are many more waiting to be told.”

That specificity is vital for asserting the essential humanity of all people. Despite the insistence of the present regime that there is “One Homeland, One People, One Heritage,” publishers have an obligation to demonstrate the remarkable and beautiful reality of many people, with many heritages, united by our common and essential dignity and rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as our own hearts dictate.

Be well and do good, my friends

Filed under: Guest Author, Uncategorized

About Edith Campbell

Edith Campbell is Librarian in the Cunningham Memorial Library at Indiana State University. She is a member of WeAreKidlit Collective, and Black Cotton Reviewers. Edith has served on selection committees for the YALSA Printz Award, ALSC Sibert Informational Text Award, ALAN Walden Book Award, the Walter Award, ALSC Legacy Award, and ALAN Nielsen Donelson Award. She is currently a member of ALA, BCALA, NCTE NCTE/ALAN, REFORMA, YALSA and ALSC. Edith has blogged to promote literacy and social justice in young adult literature at Cotton Quilt Edi since 2006. She is a mother, grandmother, gardener and quilter.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Cover Reveal and Q&A with Shifa Safadi: Sisters Alone

My Sister the Werebeast | Review

From Policy Ask to Public Voice: Five Layers of Writing to Advance School Library Policy

Penguin Young Readers Showcase: January 2026 Books

Our 2026 Preview Episode!

ADVERTISEMENT